Maqāṣid and Ethics: Foundations, Approaches, and Applied Fields

Mutaz Al-Khatib

1. Introduction

Maqāṣid al-sharīʿa (the higher objectives of Islamic law, hereinafter maqāṣid), both at the practical and theoretical levels, continue to generate debate and scholarly interest since the late 19th century. This interest was renewed in the ‘80s and ‘90s of the 20th century bringing about an influx of studies and monographs in the last few decades in various languages.

These studies reflect the interest in maqāṣid and draws attention to four key points:

First: The diversity of approaches to maqāṣid, including:

• Fiqhī approaches that explore maqāṣid in fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence), usūl al-fiqh(Islamic legal theory), and the history of Islamic legislation.

• Philosophical approaches that explore maqāṣid in the philosophy of religion focusing on sharīʿa wisdom (asrār al-sharīʿa) and the role of religion, or in moralphilosophy and the study of values.

• Political approaches both at the theoretical level concerned with maqāṣid and political theory, and at the practical level concerned with engaging maqāṣid in Muslim politics.

• Historical approaches that include accounts of capitalizing on maqāṣid for reform and legislative change within the context of modernity and revival.

• Hermeneutic approaches including exploring the role of maqāṣid in interpreting the Quran and ḥadīth.

Second: By exploring questions that go beyond the long-standing inquiry into the relevance of maqāṣid to usūl al-fiqh, maqāṣid is no longer exclusively addressed under usūl al-fiqh.

In fact, maqāṣid has turned into a headline under various fields and disciplines, a trend resulting from the engagement of scholars from outside the field of Islamic studies with maqāṣid. However, this trend was not accompanied by the theorization necessary for developing maqāṣid into a multidisciplinary field characterized by rigor and theoretical foundations.

Third: Diverse, and at times conflicting, roles have been assigned to maqāṣid given the diverse and conflicting objectives of those engaging maqāṣid, including the secularists and the Islamists, the reformists and the traditionalists, and scholars of Islamic studies and scholars of other fields (such as philosophy, politics, economics, medicine, environmental studies, social studies, engineering, architecture, and others).

Fourth: the interest in maqāṣid was marginally addressed the relation to moral philosophy with a scarcity of distinct studies directly addressing this connection. However, an ethical undertone can be noticed in the works on maqāṣid starting with contemporary scholars such as Muḥammad al-Ṭāhir bin ʿĀshūr who considered al-ḥurriyya (freedom) as one of the maqāṣid and underscored the importance of maintaining social order, and ʿAllāl al-Fāsī who held that “virtues (makārim al-akhlāq) are the criterion for all public interest and the foundation for all the objectives of Islam”. This ethical approach further gained momentum with the work of Muḥammad ʿAbdullāh Drāz where the idea of maqāṣid left its mark on his work, even if not explicitly, and matured with the works of Ṭāha ʿAbdurraḥmān and others.

2. Maqāṣid and ethics

With the great majority of maqāṣid studies being legal in nature, the centrality of maṣlaḥa (public interest) in maqāṣid rendered these studies a fertile ground for law and ethics to interact. Accordingly, a number of applied studies engaged with maqāṣid as a general ethical framework for decision making in the fields of medicine, Islamic banking, Islamic finance, marketing, and technology. These studies vary in terms of value and depth, with many lacking a theoretical foundation. This centrality of maṣlaḥa has also prompted a number of contemporary scholars to add to the five essentials in Islamic law (al-ḍarūriyyāt al-khamsa) or to expand their scope in a manner that incorporates modern values. The numerous additions and the variability in perspectives rendered maqāṣid fluid and reflective of the individual biases of the authors and of their alignment with the values of modernity, all presented under the heading of maqāṣid. Accordingly, one can detect a shift in the governing value system: from the classical one reflected in the usūl al-fiqh and maqāṣid works of the pioneers such as al�Juwaynī, al-Ghazālī, al-ʿIzz bin ʿAbd al-Salām, al-Qarāfī, and al-Shāṭibī, to a modern system evident in the works of many contemporaries on maqāṣid. These modern perspectives are but interpretations that came to respond to modern challenges through utilizing maqāṣid, an idea that was revived in the late 19th century, to argue for the compliance of political and religious reform with sharīʿa. For example, while Khayr Al�dīn al-Tūnisī and colleagues revived maqāṣid to legitimize the adoption of public goods and public institutions from the West, Muḥammad ʿAbduh revived maqāṣid to promote ijtihād and inviting Muslims to avoid following one of the four schools of law (taqlīd).

Despite the growing scholarly interest in moral philosophy in the second half of the 19th century, interest in Islamic ethics lagged and only picked up in the middle of the 20th century through various approaches: scriptural, theological, fiqhī, uṣūlī, historical, Sufi, and philosophical.

Bringing together maqāṣid and ethics presents a challenge:

First: Both fields continue to struggle today to clarify their boundaries and resolve the surrounding ambiguity. Ethics overlaps with several other fields including fiqh and uṣūl al�fiqh, rendering the question on whether these are discernably different fields a valid one. This overlap further raises the crucial question on sources and whether they are different in the different fields, which is a key consideration in differentiating a legal judgement from an ethical one. Accordingly, exploring the relationship between ethics and maqāṣid demands clarifying the boundaries and relationship between ethics and fiqh.Ambiguity has also been characteristic of the field of maqāṣid since its inception, with questions pertaining to the position of maqāṣid in reference to usūl al-fiqh: Is it a separate field or a constituent of uṣūl al-fiqh? Does it continue to be exclusive to uṣūl al-fiqh or does it serve other fields outside Islamic studies? What relationship does maqāṣid have to substantive law sources (kutub al-furūʿ fiqhiyya)? Does maqāṣid only serve to rationalize the standing fiqhī rulings of the different legal schools (madhāhib fiqhiyya), or can it serve as a source for conducting rulings even if not in alignment with one of these schools?

Second: As scholarly fields, both maqāṣid and ethics today stretch across various disciplines and fields, and as is the case with ethics, maqāṣid has become a multidisciplinary field that is engaged by scholars from various disciplines. Yet, as a multidisciplinary field maqāṣid lacks adequate theorization.

Third: Both fields, maqāṣid and ethics, have two domains: theoretical and practical. Maqāṣid is closely linked to the fiqhī rulings in despite the lack of theorization on how maqāṣid links to substantive law (furūʿ) of specific fiqhī school and to the four schools together, especially that maqāṣid, in principle, is founded on linking the universal to the particular on the one hand, and the theoretical to the practical on the other. As for ethics, as it stands today, it comprises both theoretical and applied, with the latter originally encompassing bioethics, environmental ethics, and professional ethics and expanding later to incorporate other disciplines such as politics, media, education, and others that raise practical questions in need of ethical deliberation.

In this seminar, we adopt a conception for ethics that was formulated by the convener of this seminar which encompasses three levels that seek to address the following three questions:

• What should I do (deontological ethics)?

• How should I live (virtue ethics)?

• What are the sources for addressing the aforementioned questions (meta-ethics)?

Building on this conception, the relationship between maqāṣid and ethics is in need of a thorough and in-depth investigation. Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya states that “sharīʿa is all about justice, mercy, wisdom, and good. Thus, any ruling that replaces justice with injustice, mercy with its opposite, common good with mischief, or wisdom with nonsense, is a ruling that does not belong to the sharīʿa, even if it is claimed to be so according to some interpretation”. Al-Shāṭibī also states that “sharīʿa is all about cultivation of good behavior (takhalluq bi makārim al-akhlāq)” despite the fact that he places virtues (makārim al-akhlāq) within embellishments (taḥsīniyyāt) under maṣlaḥa.

These examples demonstrate that the field of maqāṣid, in fact the field of usūl al-fiqh as a whole, is not restricted to the methodological dimension and the interpretive tools that regulate reasoning and interpretation, but rather extends to regulate human behavior and evaluate actions, as well as define the connotations of the ethical language represented by the five normative rulings, their ratio legis and their rationalization, an ethical language that offers way more than the dichotomy of good and bad (ḥusn and qubḥ). Talking about maqāṣid brings to the for a discussion on deontology and utilitarianism: that is on whether obligations are to be fulfilled for themselves or for an underlying rational goodness.

3. Themes and key questions

There are four themes for this seminar:

(1) Maqāṣid and ethics: concepts and the theoretical framework

• The concepts of maqāṣid, maslaḥa, and ethics

• A comparative analysis between Ṭāha ʿAbdurraḥmān’s proposal and the fiqhī tradition.

• Maqāṣid and teleology

• Exploring the relationship of maqāṣid and ethics in foundational and contemporary scholarly works.

• Classifying virtues under the embellishments (taḥsīniyyāt): do ethics fall under the essentials or the embellishments?

• Maqāṣid: actions, intents, and ends.

(2) Maqāṣid al-sharīʿa: ethical issues and principles.

• Benefit and the philosophy of values.

• Maqāṣid between the fiqhī reasoning (taʿlīl) and moral reasoning.

• Maslaḥa and utilitarianism.

• The hierarchy of maṣlaḥa and the relevance to the five rulings.

• The uṣūlī debate over maṣlaḥa

• The hierarchy of maṣlaḥa and the criteria for balancing benefits.

• The essentials: a historical account, the criteria for determining essentials, the potential for restricting what counts as essential, and the relevance to common morality and universal values.

• Essentials and the values of modernity: capitalizing on the concept of essentials in modern times.

• Maṣlaḥa and desires (ḥuẓūẓ al-nafs): good deeds between the objectives of the lawgiver and the objectives of the mukallaf.

• Commands/forbids and divine command theory: a comparative study.

• Religious restrainer and natural restrainer: ethics between the inner and outer

• Philosophy of permissibility: the permissible between divine objectives and the agent’s objectives.

• Maqāṣid and sources for judgement: can maqāṣid be a source for conducting rulings?

• Compliance (al-imtithāl) and virtue: can compliance with commands and prohibitions produce virtuous person?

• Maqāṣid between Ashʿarite epistemology and Muʿtazilite epistemology.

• Ethics and custom (ʿurf): virtues (makārim al-akhlāq) and good habits (maḥāsin al�ʿādāt) between stability and change.

(3) Ethical approaches to maqāṣid:

• Contemporary ethical approaches (Muḥammad ʿAbdullāh Drāz, Ṭāha ʿAbdurraḥmān, and others).

• Moral cultivation: analytical reading of one of the foundational works on maqāṣid from an ethical perspective (e.g al-Ghazālī, al-ʿIzz bin ʿAbd al�Salām, al-Shāṭibī, …)

(4) Applied cases:

Choose a specific case from one of the following fields:

• Gender issues

• Economics and financial transactions

• Politics

• Bioethics

• Human rights

• Capitalizing on maqāṣid in political Islam

• Environmental ethics

Or any other topic provided it fits under ‘maqāṣid and ethics’.

4. CILE’s work on maqāṣid and maslaḥa

This seminar comes as part of a series of activities and events held by the Research Center for Islamic Legislation and Ethics (CILE) on the topic. In May 2017, CILE held its summer school in Granada under the title “Maqāṣid and ethics in contemporary scholarship”, and in November of that year CILE dedicated a closed seminar to explore “Ethics and maslaḥa: towards a comprehensive theory”. Most recently, CILE held its winter school in January 2021 on “Maslaḥa as an ethical concept: interdisciplinary approaches”.

In addition, CILE has held some public discussions on this topic, including an interview with Dr. Muhammad Khalid Masud in 2015 on “The concept of maslaḥa and its ethical implications”, and a public lecture on “What is maslaḥa (benefit/interest)? And who decides?” in November 2017 hosting Felicitas Opwis, Jeremy Koons, and Mutaz Al-Khatib.

Lastly, this seminar comes as part of the continued work on the topic by the Methodology and Ethics Unit at CILE, under the supervision of Mutaz Al-Khatib. To date, this unit has organized three specialized seminars on Quran and ethics, modern ijtihād and ethics, and Hadith and ethics. The proceedings of the first two seminars were published in the 1st and 3rd volumes of the Journal of Islamic Ethics, and the proceedings of the last seminar are to be published soon in an edited volume. The upcoming seminar on maqāṣid and ethics comes to complement this series.

5. Guidelines for papers

Abstracts and research papers are to fulfill the following:

1. Avoid fiqhī or uṣūlī treatment that does not address modern ethical concerns.

2. Should address a specific and clear research question.

3. Should adopt an analytical approach.

4. Papers addressing the ethical theory of a specific scholar should avoid delving into biography and restrict analysis to the ethical theory itself.

5. Applied papers should include a theoretical foundation on which the applied analysis is built, bringing together the theoretical and the applied. Papers that provide general explorations or simply present Quran and Hadith quotations without engaging analytically and critically with Quran and Hadith commentaries will be excluded.

CILE calls on scholars and academicians with interest in the topic of the seminar, especially from the fields of maqāṣid, fiqh and uṣūl al-fiqh, philosophy, and applied fields (including medicine, business, economics, politics, environment, and others) to send their submissions including:

1. An abstract (300 to 500 words) that details the idea/argument, key research question, and the proposed methodology to address the question.

2. A short biography (not exceeding 500 words) that details the academic background of the researcher, their research interests, and key publications.

Scholars with successful submission will be contacted and invited to submit their full papers (7000 to 10,000 words) according to the timeline listed below.

6. About the seminar

Abstracts and papers will be evaluated by a scientific committee building on scientific criteria and taking into consideration the relevance of the submission to the topic of the seminar. A limited number of successful submissions will be selected to invite their authors to participate in the seminar to be held in Doha. CILE will cover travel and accommodation expenses.

Publishing accepted papers:

After concluding the seminar, the accepted papers will undergo blind peer review, after which they will be published in a special volume of the Journal of Islamic Ethics or in an edited volume under the Studies in Islamic Ethics Series, both of which published by Brill in Leiden. All publications will be open access.

Language for papers and the seminar:

Abstracts and papers may be submitted in Arabic or in English. The seminar will use both languages with simultaneous interpretation made available.

Timeline for submissions and the seminar:

• Deadline for sending submissions (abstracts and biographies): July 25, 2021.

• Informing scholars with decision on abstracts: August 1, 2021

• Deadline for sending first draft of full paper: October 25, 2021.

• Informing scholars of decision on submitted papers: November 10, 2021.

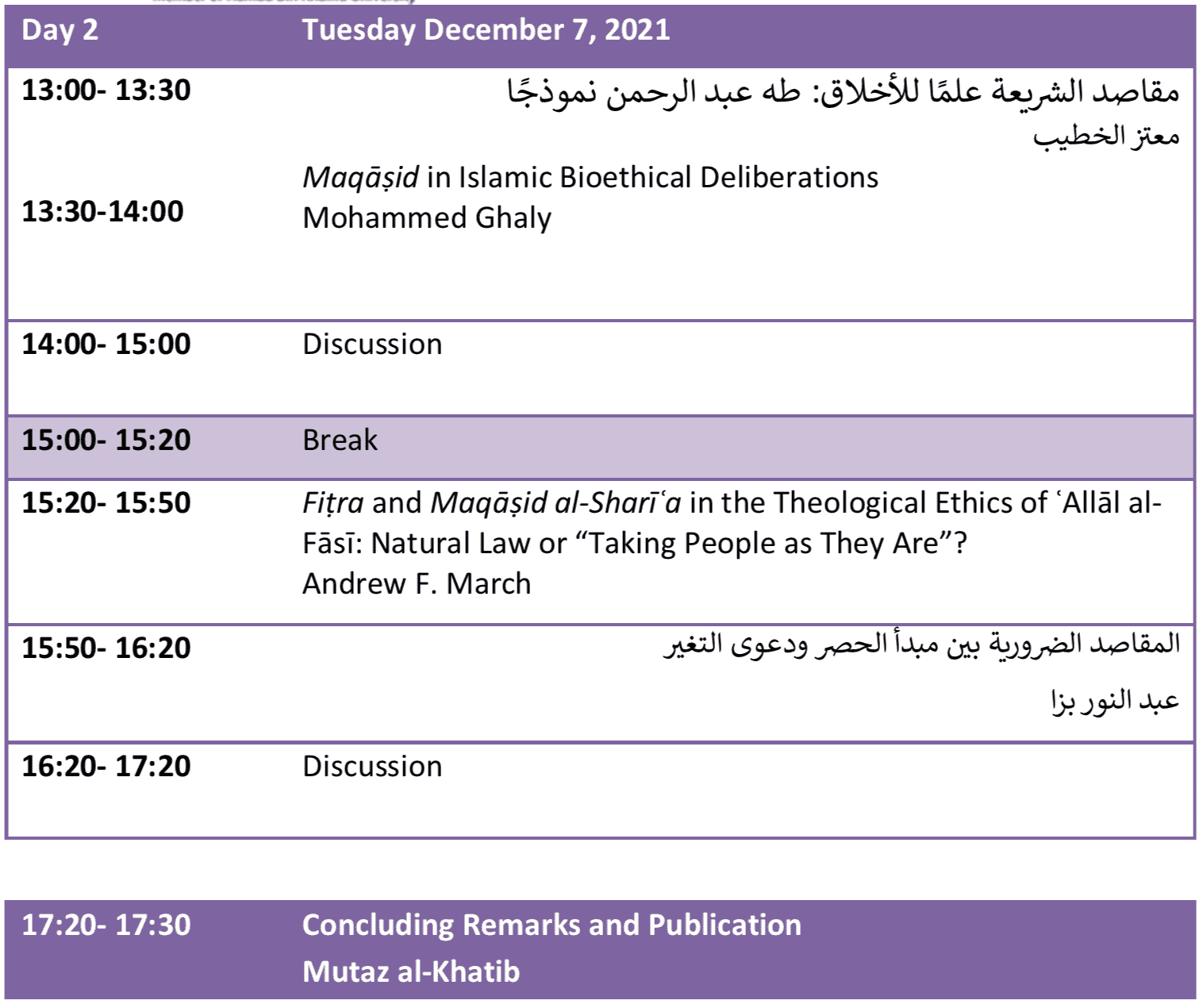

• Date for the seminar to be held at CILE in Doha: December 6-8, 2021.

• Deadline for submission of the final papers after implementing the necessary revisions: January 30, 2022.

Contact details

• Submissions are to be sent by email to submit@cilecenter.org

• For inquiries relevant to this call, please contact Dr. Mutaz Al-Khatib at CILE, College of Islamic Studies, Hamad bin Khalifa University malkhatib@hbku.edu.qa

• For inquiries relevant to the Journal of Islamic Ethics and Studies in Islamic Ethics book series, please contact jie@brill.com